Prologue: The bitter beginning of China's chocolate market

Although cocoa was introduced to Europe sometime in the 16th century it was not until the Industrial Revolution that new processes emerged which sped the production of chocolate and with that the development of an affordable mass market product. In 1824, John Cadbury, began selling tea, coffee and drinking chocolate in Bull Street in Birmingham, England. In 1847, John became a partner with his brother Benjamin and the company became known as "Cadbury Brothers”. The new firm began exporting its products as early as the 1850s.

In 1891, Cadbury sales rep William Cooper was sent on a trade expedition to China and Japan, amongst other places, arriving back in England in May 1892. Soon thereafter the brothers opened their own factory in the outskirts of Birmingham in 1897, called Bournville. In 1899 export traveler H.E. Waite made yet another trip to the East. When he retired in 1905, his area was split into three: China and the Far East; South America; and the West Indies and Canada.

Even before these Cadbury representatives set their feet ashore in China, we already hear of the first mention of Cadbury’s in 1888 making its way to the colonial outports of China: Just a few days before Christmas British trade firm Mackenzie & Co. announced in the China Herald that they have “a good assortment of English and American sweets, Cadbury’s cocoa and confectionery” available at their Shanghai premises.

The firm was started in Shanghai in 1850 primarily as a tea exporting business but in later years expanded into other categories and importation. Most likely though, they were not an officially appointed agent of Cadbury’s since they primarily dealt with the foreign residents of the treaty ports.

The first formal distributor for Cadbury tasked with the challenge to introduce chocolate and cocoa to local consumers was Rex & Co, known under its Chinese Hong name 公发英行 - “Kung-fah”. Started by Englishman Alfred B. Rex around 1889, Rex & Co was a typical small-sized foreign trading house (洋行), representing Western brands in China – foremost Pirate cigarettes by W.D. & H.O. Wills, the most famous foreign cigarette brand in China at the time and up to the 1990s! Unfortunately, Alfred died at only 51 years old in a mysterious boating accident in 1905 - a captivating story which we covered in a previous post here.

If and how much he actually managed to market and sell Cadbury’s to the Chinese during his time we do not know. There are almost no remaining records nor traces of supporting Chinese newspaper ads pre-1924. After Alfred's death, Rex & Co. was taken over by its largest British customer and partner Nutter & Co.

This English export firm was founded in 1881 by Mr. Walter Nutter senior and listed among others Lever Bros., Ltd., Cadbury Bros. , J. & J. Colman, Mellin's Food, Ltd., Blundell , Spence & Co. , Ltd. ("paint and oil makers") and J. McCallum (distillers of “Perfection Whiskey") as its clients. While the eldest son Walter Nutter junior managed the business with his father back in England, the younger son Percy John Nutter was sent to Shanghai to take over and integrate the remains of Rex & Co.

The Shanghai firm was renamed to Walter Nutter & Co, but its Chinese trade name “Kung-fah” was kept, building on its well-established reputation among Chinese merchants and trade partners.

Meanwhile, in Birmingham, Cadbury Brothers introduced the stronger Bournville Cocoa powder line in 1906. Named after its factory location, this product in particular provided the basis for the company's rapid pre-war expansion incl. to the Far-East.

Once more though Cadbury’s China distribution business was soon struck by another premature death when Walter Nutter junior, who had by now taken over the management of the family business, passed away in Britain at only age 38 in 1912. His brother Percy was forced to move back from Shanghai, handing over the development of the China market to the second in line Mr. H. H. Fowler.

THe Localization Menace: A closer Inspection of our poster

This now brings us to the approximate time of our Cadbury’s chocolate calendar poster. Upon closer look it reveals many interesting details about the firms involved, the state of the cocoa business in China at the time, prevailing aesthetics and the ever-present translation and localization challenges of Western brands.

Firstly, and least surprisingly, the calendar poster features a classical Han dynasty scene, painted by an anonymous artist and portraying military general Guan Yu with Diao Chan, one of the Four Beauties of ancient China. Guan Yu's life was lionized and his achievements glorified to such an extent after his death that he was deified during the Sui dynasty. His deeds and moral qualities have been given immense emphasis, making Guan Yu one of East Asia's most popular paradigms of loyalty and righteousness. Thus, this very common motif in early 20th century Chinese advertising, embodies a time when Western brands were still trying to appeal to traditional themes and sentiments, very much opposed to the late 1920s when the turnaround to marketing a modern Western lifestyle occurred. The predominant traditional Chinese style of key visuals, even in 1915, can further be explained by the after-effects of the anti-Western Boxer Rebellion 1899 to 1901, the boycott of American products in 1905 and finally the overthrow of the Qing dynasty in 1911, which all appeal to the patriotic feelings of the Chinese consumers.

The header of the poster is revealing in several ways. The first line reads “本厂精制补身果果粉及卫生巧格力糖”, which translates to “This factory produces refined tonic cocoa powder and hygienic chocolate candy”. Hygienic or “weisheng” being a very important key word at the time about which you can read more on our blog post here. The most interesting fact about this sentence though is the Chinese translation of cocoa to 果果 “guo guo”, literally meaning “fruit fruit” (arguably maybe influenced by the Shanghainese dialect pronunciation "ku ku")! This truly shows how early Cadbury and its Chinese distribution partners Kung-fah were at the time, when they literally had to make up a makeshift transliteration for cocoa by themselves. By the 1920s a modern and more fitting translation was introduced, which to this day marks the proper Chinese word for cocoa: 可可 „ke ke”. Likewise, the sentence uses the characters 巧格力 „qiaogeli” as a transliteration for chocolate, as opposed to the later and now formally established Chinese word 巧克力 “qiaokeli”.

Next up we have in bold letters the first Chinese name of Cabury’s “英国克拔来氏厂”. A frankly even worse transliteration than “guo guo”. Although the Chinese pronunciation of 克拔来 “ke ba lai” does sound somewhat like Cadbury (even more so in Shanghainese), it carries absolutely no meaning to a Chinese native (gram pull come!?).

The third and last part of the header reads “总经理上海公发英行分售处各洋离货号” and promotes the General Representative of Cadbury’s in China 公发 Kung-fah aka Walter Nutter & Co, formerly Rex & Co. Never let your distributor create and market your Chinese brand name, held as much true then as it still does today. Luckily for Cadbury, the professional ad men came in eventually but more on that later.

Let’s finish the analysis of the poster with the footer. In the lower right corner the name of the printing company is listed as Norbury Natzio Co Ltd Manchester, London & Shanghai. Above that the whole range of Cadbury’s products and sub-brands are lined up in – to the Western eye – an impressive array. Not so much for the Chinese consumer of the time: Neither did she or he know what “guo guo” or who “Kebalai” was, nor could they visually make out what kind of products were even advertised. None of the packages are opened and reveal the actual content of the boxes – a learning Carl Crow famously wrote about in his experience working with Sun Maid Raisins. The fact that most of the Cadbury packaging displayed on the poster were cylinder shaped, was guaranteed to mislead consumers into thinking this was an advertising for cigarettes which then were commonly sold in such round tin cans. Lastly, the product selection makes absolutely no sense to advertise to Chinese consumers. Be it in the hinterlands or even in the treaty ports: good luck shipping solid chocolates all the way from Birmingham to China in the 1910s. Even nowadays cold chain logistics is barely able to transport e-commerce chocolate orders during the boiling Chinese summer months…

In summary, this poster was nothing less but a disaster and a testament of the ignorance of both Cadbury and its Chinese distributors about the nature and state of the Chinese confectionery market. Except for a few local ads in Tianjin by another distributor, Twyford & Son (泰孚洋行), in Tianjin, the Chinese newspaper archives show no print ads during that time, supporting awareness building for neither the Cadbury brand nor the globally emerging cocoa or chocolate FMCG category. We are safe to say, this first sweet dream of making millions off Chinese with cocoa quickly melted away like a chocolate bar in the Shanghai summer heat.

Interlude: Attack of the Clones

The gap in the market for chocolate bars was soon filled by other Western enterprises producing locally in China.

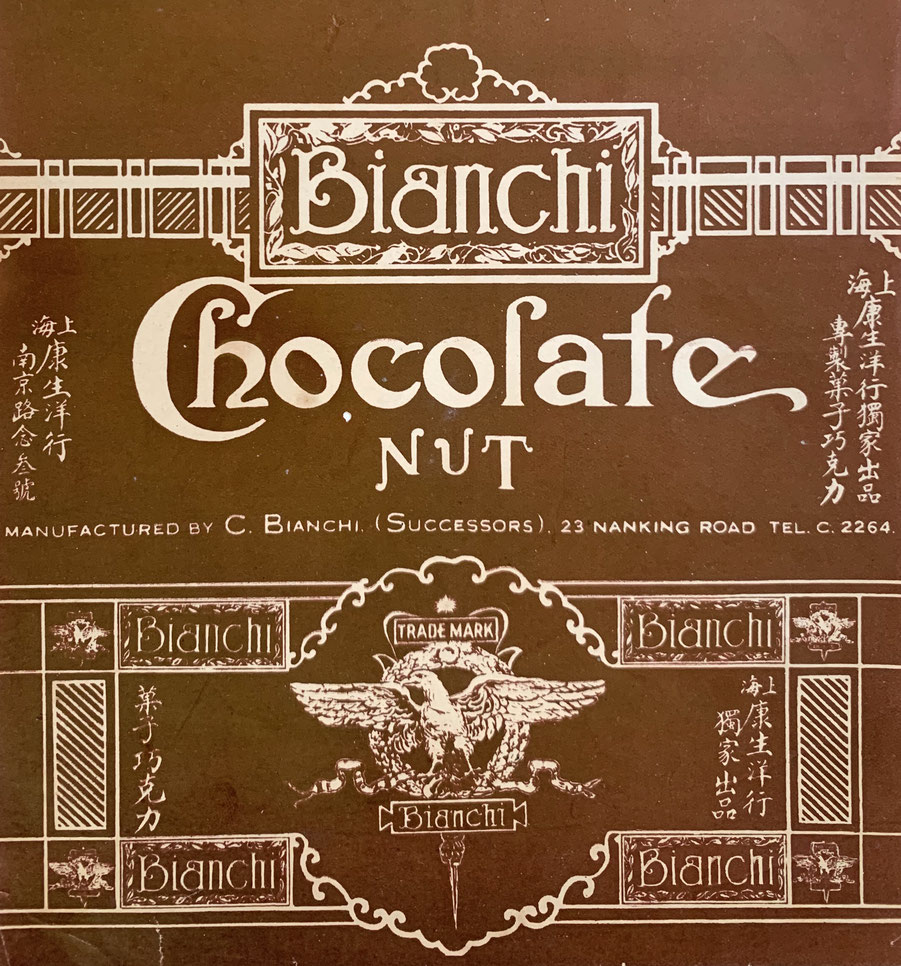

One of the earliest, if not the earliest Western confectionary in China, was C. Bianchi's. The Italian establishment was originally founded in Shanghai in 1898 but changed hands and locations many times over the years.

It's golden period though was undoubtedly under the leadership of long time Shanghai resident Attilio Ferrari, who opened the prominent and most remembered location of Bianchi's on 23 Nanking Road in 1918.

Another candidate for the first foreign bakery and confectionary in China is the Greek Tientsin Bakery “Karatzas” on the corner of Rue Dillon and Rue de France. It was there where Albert Kiessling first worked in 1905 before he launched the famous German Kiessling & Bader Café in 1906. Other early China chocolate pioneer were American Sullivan's Candy Store founded in 1908 and the Scottish confectionary chain James Neil&Co founded in the 1910s in Shanghai.

A new Hope

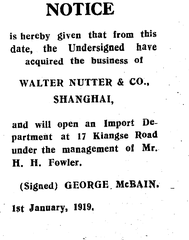

In 1920 Walter Nutter senior passed away in Essex. With the Great War’s end, his brothers’ premature death and his father’s failing health the only remaining son Percy already in 1918 felt he had no choice but to sell the China operations of Nutter & Co. And so it was announced on January 1st 1919 in the North-China Daily Herald that famous British conglomerate George McBain (麥邊洋行) had acquired Walter Nutter & Co. and through that had formed its own import department. Manager of the newly created division became H.H. Fowler, Nutter & Co’s former Managing Director.

Likewise, all the brand representation accounts were taken over including Cadbury’s, who was now in the hands of a much larger and professional organization with George McBain. Just in time for the roaring 20s and the beginning of the Golden Age of foreign brand advertising in China.

As a first step, sometime between 1919 and 1923, McBain changed Cadbury's Chinese name to "kan da bao li" (坎大保里) as well as started using a different - and arguably slightly better - transliteration for cocoa, now written as "kou kou fen" (寇寇粉), as can be learned from a Cadbury Cocoa Essence brochure from the MOFBA collection dating to that timeframe.

A Cadbury's cocoa essence sales brochure in Chinese created by George McBain between 1919 and 1924. From the MOFBA collection.

After some market research and re-assessment in 1923 by the new Cadbury Far-Eastern sales rep Mr. Davies, up-and-coming American ad man Carl Crow was brought in to manage all advertising and public relations for Cadbury’s in China. Crow opened his agency Carl Crow Inc. in 1919 and had prior experience and references with a similar client, Sun Maid Raisins. Together an entirely new strategy was drawn up for Cadbury’s in China: Firstly, an even more professional transliteration for Cadbury’s was created which is still in use today: 吉百利 ”jibaili” meaning something along “A hundred fortunate benefits”. Secondly, the emphasis was no longer to be put on the umbrella brand but on the demonstrated top seller Bournville Cocoa. For that an equally excellent Chinese name was chosen in 本味可可粉. “Benwei”’s characters translating to “original flavor” and cocoa now being properly spelled “ke ke”. Carl Crow and Cadbury’s can surely be credited for popularizing the Chinese word for cocoa still in use today, although Crow might not have been the one to coin it since "ke ke" was already mentioned in Chinese newspapers in as early as 1918.

Lastly, and most importantly since both the category of cocoa powder as well as Bournville as a brand were as good as unknown to Chinese consumers, Carl Crow decided on a new value proposition and messaging for the delicious drink mixture: health-appeal. Rather than taste, the healing properties of warm cocoa were to be advertised. Here is Crow in his 1937 classic book "400 Million Customers" on how he came up with this seemingly genius idea:

"Several years ago, we were putting on a fairly big campaign for a British cocoa manufacturer who wanted to make the Chinese a nation of cocoa drinkers. (....) we sent a second copy of the directions a few days later ~ with a letter which politely expressed the hope that the recipient had tried the cocoa and had liked it.

The first response came from a railway official at Hangchow. He said that he had been suffering from sleeplessness and indigestion for years and that he drank tremendous quantities of tea in order to keep himself going and get through his daily work. After trying out our samples of cocoa, he had bought a full-size tin, discontinued drinking tea, had been drinking cocoa instead, and now, after a fortnight's change in diet, he was sleeping soundly, his digestion was improving, and he felt better than he had felt for years.

For an advertising agent to find a letter like that in his morning's mail is like finding an unexpected gold piece in a pocketful of coppers. (...) It seemed to me that here was the basis for an entirely new advertising appeal in which we would stress the health-giving properties of cocoa."

Carl Crow billboard advertisements for Cadbury's Bournville cocoa powder. Source: https://madspace.org/

The "several years ago" Crow referenced in 1937 was in 1924 and through-out early 1925 when we can find a heavy advertisement push of both outdoor billboards and adverts in the major Chinese newspapers created and booked by Carl Crow Inc. Crow also pulled another one of his tricks for Bournville that he had previously used for Sun Maiden Raisins and boasted about once more in "400 Million Customers": a cocoa recipe contest with a prize of 100 yuan for the first, 50 yuan for the second and 10 yuan for the third place. Notably the Chinese word for chocolate (巧克力 qiaokeli) is not mentioned in any of the ads. In fact the first time this modern transliteration was mentioned in Chinese sources is 1923 when the Chinese company 馨大新公司 (Xindaxin) filed a trademark infringement case regarding its Train brand of chocolates (火车牌 ).

Interestingly, in parallel with Bournville, Crow and Cabury's also decided to promote J.S. Fry & Sons in China, a previously independent chocolate manufacturer that was acquired by Cadbury's in 1919.

While Cadbury focused on promoting cocoa powder exclusively with it own Bournville brand, J.S. Fry was intended to give chocolate bars and chocolate candies another shot in the Chinese market. Arguably, not entirely a bad idea since J.S. Fry was actually founded almost 85 years prior to Cadbury's in 1759 and was a true pioneer in hard chocolates: In 1847, Fry's produced the world's first solid chocolate bar and also created the first filled chocolate sweet, Cream Sticks, in 1853.

Now under a single group ownership both brands were represented by George McBain in China as calendar posters from the MOFBA collection reveal. Presumably Carl Crow Inc. was responsible for the visual creation of the 1925 edition of the calendar. Even though on these posters the packages are opened with chocolates visible inside or besides them and the lady actually holding a piece of chocolate to her mouth, the actual Chinese word for chocolate "qiaokeli" is still not to be seen on the poster.

Be it as it may, given its production facilities being only situated in Britain and the lack of cold chain logistics, the idea of marketing hard collocate bars still remained challenging and consumers favored locally producing Western establishments such as the aforementioned Bianchi's, Kiessling, Sullivan's and James Neil. The latter already maintained two locations of his confectionary by 1916, one in the Astor House building and another on Bubbling Well Road.

Various Cadbury's Bournville cocoa print ads from 1924 and 1925. The last three from the MOFBA collection.

Likewise unfortunately, after one year of intense advertisement still barely any Chinese were in fact buying Bournville cocoa powder. Cadbury’s HQ was furious. Not only didn’t the promised sales materialize, but Cadbury also strongly disagreed with Crow’s strategy to position their products as tinctures for chronic indigestion or insomnia… As a direct consequence the advertising manager of Cadbury’s, Mr. W. Davies, was once again sent “on a year’s tour of the Far-East”, arriving in Shanghai in September 1925. We can only imagine how the conversation between Davies and Crow went down, but even in Crow's book, the "godfather of foreign brand advertising in China" admitted this devastating defeat:

"We were rather proud of ourselves when we wrote to the British manufacturer telling him what we had done. Unfortunately for us, the manufacturer did not share our enthusiasm. He did not approve of anything we had done. Though he wrote to us with some Quakerish restraint, his words were biting enough as they were, and much could be read between the lines. The reputation of his old and respectable firm had been dragged in the mire by our blatant and unethical advertising. He took no more chances with us but turned the advertising over to another agency who could be trusted to maintain the respectability of the firm no matter how much that high estate might cost in the loss of sales opportunities."

In all fairness, though it was not only Cadbury's who burned their fingers with hot chocolate in China during the 1920s.

Other Western chocolate or cocoa powder brands, such as Swiss Nestle, French Menier or American Golden State Chocolate, suffered the same fate.

Just like Cadbury's they had appointed distributors, shipped products and invested in advertisement campaigns that unfortunately ended up generating little to no sales.

Even the mighty Mars Candy Factory, Cadbury's biggest American competitor founded in 1911, did not enter China until after the Second World War.

Instead a Jewish immigrant called Zukerman had in parallel setup the "The Mars Chocolate & Candy Factory" in Harbin in 1925. He was also the founder of the famous Mars Café who in 1941 would later setup a branch in Shanghai with another Jewish refugee. It is unclear if the naming of the Harbin Mars Café and chocolate factory was coincidental or in fact deliberately chosen after the US company of the same name.

Candy wrappers from the Mars Chocolate & Candy Factory Harbin. Source: http://blog.sina.cn/dpool/blog/s/blog_4e2e37710100lhld.html

Harbin Mars, with packaging strongly influenced by Russian design elements and with bilingual Russian & Chinese wording, catered towards the large Russian population across Heilongjiang and elsewhere, but became quite popular among all Westerners in China. Beyond them though, Harbin Mars did not achieve any notable traction among Chinese consumers.

A very rare 1920s Chinese (Harbin) Mars Chocolate Candy box. The China distributor listed on the logo is "SWEET TSI KUNG MEET CO. LTD." From the MOFBA collection

Despite the utter failure in China, globally Cadbury’s business was flourishing and by 1930, Cadbury, now a public company, was the 24th-largest British manufacturing company as measured by estimated market value of capital.

The Force Awakens

Also by the 1930s domestically manufactured chocolate was all the rage in old Shanghai and other treaty ports where numerous new - mostly foreign run - producers had emerged such as the Olympia, the Russian Astoria Confectionery and French Marcel's, catering primarily to the Western residents.

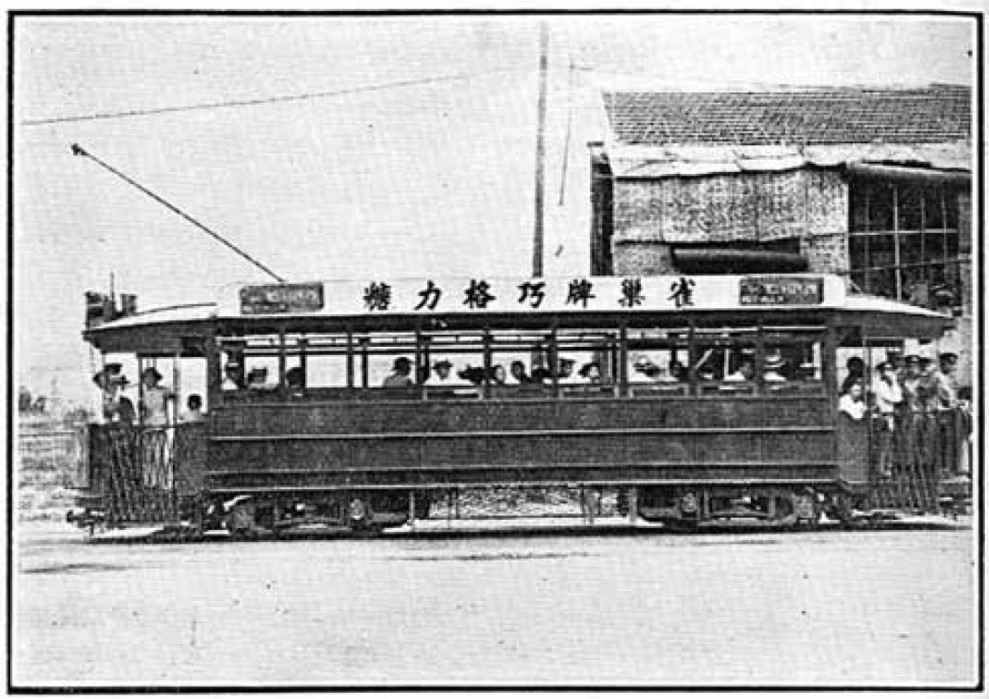

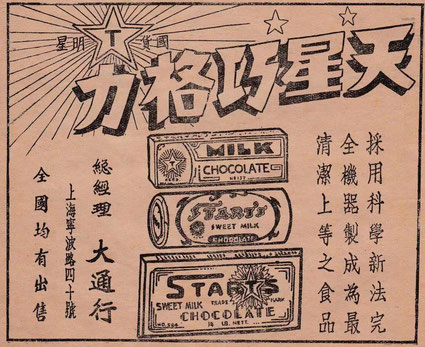

One notable exception was the Start Chocolate Shop (天星巧克力) founded by notorious Chinese food entrepreneur Lin Shengfu (林笙甫) in 1932. Not only did it maintain a flagship store on 751 Bubbling Well Road serving chocolates, candies and bubblegum, it also advertised nationwide distribution of Start's milk chocolates via its distribution company Datong (大通行). Unfortunately even such early Chinese innovators could not develop a mass market among its fellow countrymen for chocolate yet and the Start's shop soon ceased operations again.

A more successful Chinese enterprise was the M.Y. San Confectionery (馬玉山), with among others a prominent branch on 37 Nanking Road and founded by Hong Kongnese entrepreneur Mar Yuck-San. While they did sell chocolates, the company was primarily focused on cookies - a smart choice that matched consumer taste and was much for suitable for mass distribution in terms of temperature resistance.

Picture credits: https://avezink.livejournal.com / https://pastvu.com/p/1155180 / https://pastvu.com/p/1414061

After the previously mentioned Bianchi's and James Neil & Co, also Shanghai's famous ice cream producer Henningsen Produce entered the chocolate market with its Hazelwood brand.

Even more impactful however, was the American "The Chocolate Shop" - immortalized in countless memoirs of old China. J. G. Ballard for example — the British author of the novel “Empire of the Sun” based on his Shanghai childhood — fondly recalled “Saturday ice cream sundaes at the Chocolate Shop”.

The restaurant & confectionery emerged out of Sullivan's Candy Store founded in 1908 and last located on 36 Nanking Road (later 107). By 1933 it expanded to a second location on 883 Bubbling Well Road with it's "Western Branch". Both were owned and managed by the Bakerite Company which had bought an old textile mill in Shanghai that had gone out of business and had made it into a factory to manufacture food, making "candy, cookies, ice cream, and all the good stuff", before it acquired Sullivan's in 1921. In the 30s the Chocolate Shop Nanking Road location became the meeting point for an illustrious group of young Americans. Over milk shakes, radicals like Harold Isaacs, Agnes Smedley and Edgar Snow (he met his wife in the Chocolate Shop) debated China’s future. J.B. Powell, the crusading editor of the China Weekly Review, “Judge” Allman, the hillbilly-turned-lawyer who presided over the Mixed Courts and American businessmen like advertising pioneer Carl Crow, joined with American missionaries, chorus girls and the odd conman to enjoy the only ice-cream sodas in the city. In 1935 infamous writer Emily Hahn caused a sensation when she walked into the Chocolate Shop with her pet gibbon Mr. Mills draped across her shoulders.

An original 1930s box from "The Chocolate Shop" in Shanghai. From the MOFBA collection.

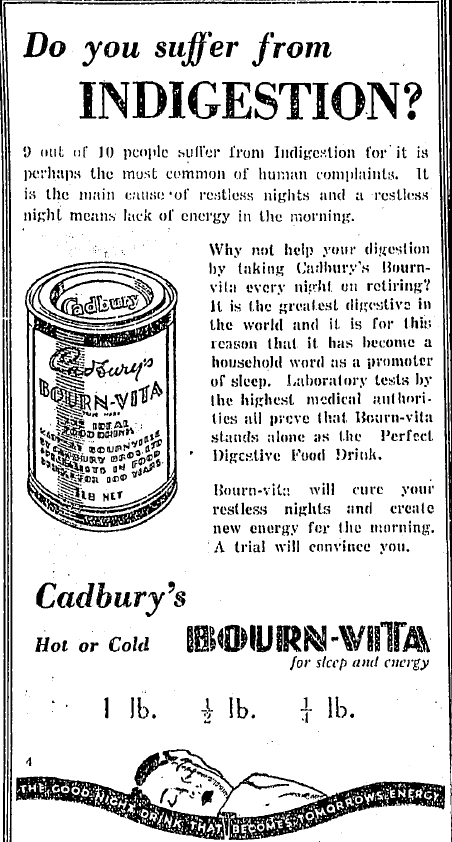

As a consequence of the 1930s confectionery boom, Cadburys tried once more to grab a piece of the sweet Chinese chocolate pie: First in 1931 with Chinese advertisements (incl. for Fry's chocolate nuts!), represented by trading firm Geddes & Co and then between 1935 and 1937 with numerous adverts in English language newspapers targeting the foreign population of the concessions and outports of China. Listed as sole agent for the latter was Jardine Matheson – one of the oldest and the largest foreign trading house in China. Seemingly having learned nothing from its past experience however we once more see Bournville (or to be precise its latest iteration Bourn-Vita) advertised as a “digestive against indigestion”. Another rather pathetic attempt was to jump on the mass market trend created by Coca Cola promoting Bournville as a “Cola Drink, approved by the Shanghai medical profession and by doctors throughout the world”.

With the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, also this final desperate attempt to break into China slipped through Cadbury’s fingers like fine cocoa powder. The occupation of vast parts of China and the “Solitary Island” period of Shanghai meant that international imports were increasingly restricted.

Additionally, during the Second World War the Bournville factory was turned over to war work and the British wartime rationing of chocolate only ended in 1950 when normal production resumed.

Cadbury's Swiss competitor Nestlé continued to advertise their chocolates in China throughout the late 1930s & early 40s although their supply was also very limited and sales were negligible compared to their powdered milk.

The same goes for Swiss Tobler (producer of the now famous Toblerone) which made a short foray into China in 1938.

Original late 1930s Nestlé Chocolate bar box. From the MOFBA collection

A price list from the grocery store Zung Lee & Co. from our collection shows, that by early 1941 there were barely any imported foreign chocolate brands available anymore in Shanghai.

Supply was mostly limited to local producers such as Henningsen's Sweetie brand or Start's Chocolate.

The Empire Strikes Back

During the Japanese occupation of the International Settlement from late 1941 to 1945, American and British assets were seized and their respective nationals eventually imprisoned in internment camps.

It was during this window of time that Morinaga & Company, Ltd. (森永製菓株式会社), Japan’s oldest and most acclaimed chocolate producer since 1899, started a factory in Shanghai together with a confectionary shop on Szechuen Road in Honkew district. It had already set up a small branch in 1939 on Canton Road, but was now preparing for it's big expansion.

However with the Japanese surrender in August 1945 also Morinaga's ambitions to establish a chocolate empire in China came to an abrupt end. In the immediate chaos of the post-war months, the cocoa and chocolate market was in disarray with neither Western nor Japanese businesses able to manufacture domestically nor import.

Revenge of the Chinese Enrepreneurs

Now, you might wonder why no local Chinese businessmen jumped on this opportunity after the end of the war. An excellent question, and the answer leads us back to an old friend, featured in one of our previous articles: Chang Pao Cun. In late 1945, and in addition to his C.P.C. coffee factory, he opened the "Chinese United Bakery" plant, producing C.P.C-branded breads, candies, moon-cakes and… canned cocoa powder!

When his businesses were nationalized in the 1950s, the factory continued to be the only domestic manufacturer of cocoa powder under the “Shanghai brand”. An iconic product very well remembered by older Chinese to this day.

This not only made Chang Pao Cun the Shanghai “Coffee King” but also the short-lived "King of Chinese Cocoa".

Likewise also the local Shanghai A.B.C. company re-entered the chocolate business during that time.

In this brief post-war period of Nationalist-controlled Shanghai between 1946 and 1949, chocolate shops, cafés and confectioneries in fact experienced a massive comeback.

The 1947 Shanghai Telephone Directory for example lists over 200 confectioners with most of the old classics such as Astoria, Bianchi's, Chocolate Shop, Marcel's or Olympia still in operation. Most notably absent is James Neil&Co, who's Scottish founder had passed away in 1937 and sometime after the war in around 1948 his famous Shanghai chocolate shop chain, with at the peak 5 locations, was shut indefinitely.

The Shanghai branch of the Harbin Mars Café also re-opened after the war and in fact on top established a local plant for the Mars Chocolate & Candy Factory on 100 Chungcheng Rd. West (the short-lived name of the former Great Western Road, now called Yan'an West Road).

Finally, in 1946 even the original US Mars Incorporated, secured its various trademarks in China, preparing to now formally enter the market, which from Carl Crow's heyday of "400 Million Customers" in 1937 had now grown to over 500 million.

But once again, in the bitter-sweet chocolate history of China, such sugar-coated pipe dreams would soon be replaced by a harsh new reality.

After the Communist liberation in 1949 the Chinese market was closed off for "bourgeoise" products such as chocolate and confectionary for the next 30 years.

The Return of the "Big Five"

Out of the “Big Five” chocolate brands Nestle and Mars were the first to enter China again in the 70s and early 80s. Ferrero, Hershey and Cadbury followed soon thereafter and once more attempted to introduce chocolate into the Chinese diet evolving the image as an exotic curiosity. And once again they were challenged by the importance of finding a meaningful way of introducing the good with surprisingly poor results to this day: According to the Association of Chinese Chocolate Manufacturers, consumers eat 70g of chocolate per capita every year. This figure is dwarfed by 2kg in neighboring Japan and South Korea. In Europe, the average consumption of chocolate is 7kg per person per year.

Globally in 2020 China only accounted for 3% of chocolate consumption and in 2018, retail sales of chocolate products in China amounted to only 11.2 billion U.S. dollars. Since 2010 Cadbury's is part of Kraft Foods, who's confectionery business was renamed to Mondelez in 2012. As of 2020 it holds a distant number 6 position in China in terms of market share (3%), far behind Godiva 3%, Hershey 4%, Nestle 8%, Ferrero 22% and Mars 34%.

Many thanks to Lawrence L. Allen, Diane Wordsworth, Cecile Armand and Paul French for their brilliant work on the history of chocolate in China, Cadbury's, Bournville and Carl Crow, as well as to Katya Knyazeva and Historic Shanghai for contributing to this article.

Write a comment